Imagine listening to birds without the sounds of human machinery in the background. That’s what our world was like when Aldo Leopold was alive.

In 2012, ecologists Stan Temple and Christopher Bocast from the University of Wisconsin-Madison recreated a 1940 soundscape at Aldo Leopold’s shack in Salk County, Wisconsin. The project was amazing because they didn’t have a recording from Leopold’s time. Instead they built it from his field notes.

Every morning Aldo Leopold listened to the birds and wrote detailed notes of the songs he heard, where he heard them, and the light levels when the birds first sang. Using his notes, bird song recordings from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology’s Macauley Library, and newly recorded background sounds from Wisconsin, Temple and Bocast completed the soundscape.

The result is nothing like the place today. The habitat, birds, and insects have changed and now there’s the constant hum of an interstate less than a mile away.

To get “clean” background sounds Temple and Bocast searched for a quiet place in Wisconsin. It was very hard to find because, as Temple points out, “in the lower 48 states, there is no place more than 35 kilometers [21.7 miles] from the nearest road, making it nearly impossible to tune out the hum of human activity, even in places designated as wilderness.”

I’m familiar with the problem. I’m used to noise near my city home but I go to the woods to be quiet and listen to nature. In the last 15 years I’ve noticed an increase in human-generated sounds in the woods. It’s impossible to avoid the sound of cars, trucks, trains, motorcycles, airplanes, chain saws, all-terrain vehicles, boats and jet skis.

I don’t like it. Perhaps I’m not alone.

On Sunday I watched a flock of robins in the trees along the Bridle Trail in Schenley Park, directly above the Parkway East. I tried to locate the birds by sound but could not hear them over the roar of the interstate.

The birds probably couldn’t hear well either. It was more than annoying. It was stressful.

I wonder what they think of ubiquitous human noise.

Click on the photo above or on this news article at University of Wisconsin-Madison. Then scroll down and click on the Soundscape link to hear what Aldo Leopold heard.

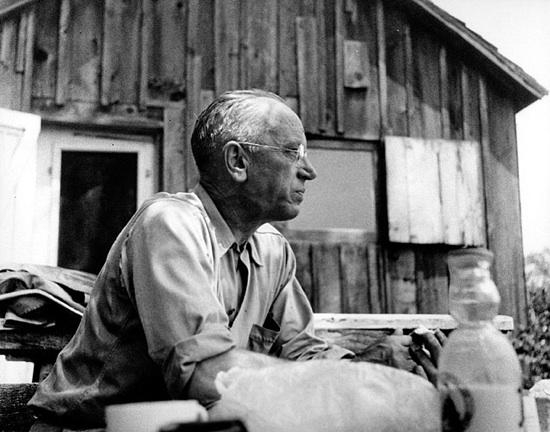

(photo of Aldo Leopold, courtesy UW Digital Archives. Click on the image to read the article and listen to the recreated soundscape.)

Loved this. Grew up in rural Gibsonia. No place like quiet. I never thought about this so much lately but I will stand & listen today wherever I am and realize there is probably no quiet in my life where you just hear birds and beings. No wonder we all feel so stressful. So many things we are losing and don’t realize it until wondrous adventurers like you remind us of what we are losing and we must all remember the children deserve it also.

I recently went with two other birders looking for common nighthawks. We met in a mall parking lot overlooking a highway. I didn’t enjoy it much at all with all the high levels of noise, traffic, no scenery, no peace, no quiet. It helped me define what kind of a birder I am! I love the Wisconsin project. Recreating the soundscape from 1940. Wow. How things have changed. Sad. Wonder what it will be like in another 60 years….

This also reminds me of the first time I went home (small town Ohio) after moving to a city 4 miles outside of Boston. I had to adjust to the traffic noises when I moved to Boston, and when I went home again, the birds kept me awake!

Thanks, Kate. Noise pollution, just like light pollution, has a negative impact on our ability to enjoy the world around us. There was an interesting article about a year ago describing how urban birds adjust their songs to be heard over the city noise. They have to adjust to competd with low-frequency sounds, resulting in differences between the songs of urban birds and their country cousins. NPR reports on the study here: http://www.npr.org/2011/12/24/144102328/to-flirt-in-cities-birds-adjust-their-pitch

Very interesting. I’m not a fan of the sounds of nature being drowned out by our human sounds, but I have to admit that sometimes I wish the birds could be quieter in the wee hours in the spring!

Is there a listing of the birds in this clip and when they enter? I’m hearing American Robin, Field Sparrow (slightly different call than we hear here in the east), Black-capped Chickadee (or maybe Tufted Titmouse), Common Crow, and a few others that I should know but cannot place right now. Out of practice on my birding by ear…

Want to add Northern Cardinal in the background, possibly a Brown Creeper (faint), is that a Lark Sparrow in there? Easter Pee-Wee and Catbird for sure. Mourning Dove. Ring-necked Pheasant! Wood Thrush? Not sure what the harsh raspy one is (another call of the RNP?) Is the warble a House Finch? Is that a Red-winged Blackbird ending the clip?