January 20 – February 11 is the time for Pennsylvania’s Winter Raptor Survey (WRS) when volunteers drive prescribed routes and tally the number of raptors they see.

Many volunteers post their counts on PABIRDS where we learn that our most numerous winter raptors are red-tailed hawks. (No surprise there!)

The reports include weather and snow cover conditions because this affects the number of raptors seen. This year few routes have snow.

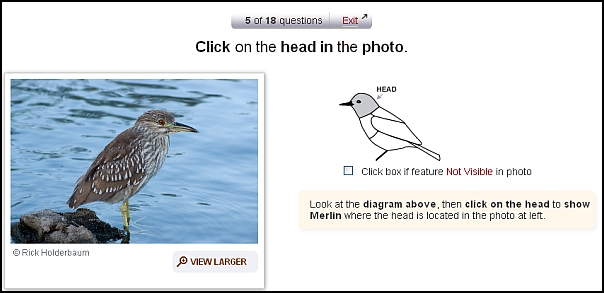

In a snowy year rough-legged hawks move south in Pennsylvania. They breed in Alaska and Canada and winter in the Lower 48. They’re found hunting in open meadows and brushy areas for mice, voles and rabbits. But only where there’s snow cover. If there’s snow, the rough-legs are here. If not, they stay up north.

Two years ago we had a lot of snow — so much that it was hard to drive the routes. (Remember the two feet of snow February 5-9, 2010?) This year it’s easy to drive but the birding isn’t as good.

I’m not asking for a return to the snow of 2010 but snow in moderation would be nice, if only for rough-legged hawks.

Steve Gosser was lucky to see this one at Pymatuning on January 14.

(photo by Steve Gosser)